|

In Search of a Body an Art Mystery by Warren Criswell A presentation I gave for David Bailin's art students at Hendrix College, Conway, Arkansas in September 2011 |

||

| 1. Early Work A “body of work” usually means a collection of related works, connected by some characteristic or principle. I can never deliberately carry out a program like that. I sometimes think I have a series, I can see all the paintings or drawings in my head, stretching into the future. Once I even proposed to a gallery a show devoted to such a series, but after the first painting the rest of them disappeared. I’ve done a lot of series of one. So where is the body? I can’t seem to start with an idea, in the intellectual sense. It has to be an image that comes unbidden out of god knows where and ambushes me. But I find that sometimes, after a many of these ambushes, the images do reveal themselves to be part of a whole. And why not?—since they all came out an encounter between my unconscious and something I saw or heard in the world. |

||

|

[CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE] |

|

|

"The

Grand Inquisitor" is a chapter in Dostoyevski's novel The

Brothers Karamazov, in which the young monk Alyosha tells

his brother Ivan a parable about a second coming of Christ during

the Spanish Inquisition. During the interrogation, after which

the Cardinal intends to burn him at the stake, Christ says nothing.

The Cardinal does all the talking. I'm seeing this now as a right-brain

/ left-brain thing. The Cardinal has the Book, his body of work.

His prisoner is only an image. But I wasn't thnking that while

working on the painting. I had only the image. And then there was Francis Bacon and Sartre. I was interested in the origin of self-consciousness. If I am conscious of myself, who is it that's conscious of whom? There must be two of me. This is the origin of the doppelganger, a theme which still haunts my work. The double can be the conscience-- the Grand Inquisitor--or it can be the irresponsible person you would like to be, running amok, naked and free, like Adam and Eve before the Fall. I think the broken egg in the paintings represents that split, the birth of the self, the loss of innocence, the expulsion from Eden, the outbreak of war, the beginning of pain and pleasure. In other words, the beginning of being human. |

| There's actually

a forerunner of this in a much earlier painting, my Dies Irae,

a landscape which includes a billboard advertising Francis Bacon,

with one of Bacon's screaming popes. You'll see it in the video.

But none of this was planned, that's my point. Just as a painting or drawing seems to create itself, so does a body of work. So here's the montage... |

Warren Criswell, Dies Irae (detail), 1987 |

|

Early Work 1979 - 1995 from Warren Criswell on Vimeo. |

|

|

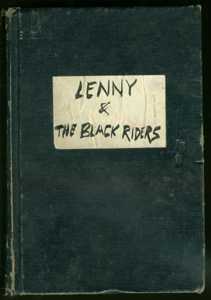

2. Lenny & the Black Riders

|

||

|

OK, sometimes I broke the rule, give me a break. But the point, again, is that I wasn't thinking thematically, only technically. But this was a bound volume, not a notebook

that I could rip pages out of when a drawing went bad, so I was

extra careful and pretty soon I realized the thing was turning

into a book -- but about what I didn't know. I began to go back

and develop my pencil sketches with sumi ink washes, or pastel

or sepia ballpoint or combinations of the three. For the night

scenes I used liquid frisket and black sumi. Later, to give it some structure -- as if

I'd planned it from the beginning -- I divided it into three

parts. The Verdi concert gave me the idea of taking titles from

the Roman Catholic Requiem -- Krie (Lord have mercy), Dies Irae

(day of wrath) and Lux Aeterna (eternal light). But, as I said

at the beginning, I'm no good at series and long term projects,

so while I didn't abandon my sketchbook and always intended to

finish it someday, other pursuits pushed it into the background.

Flipping through those old pages, I was amazed at how relevant much of it seemed now. The 1982 invasion was the beginning of suicide bombing and the birth of both Hezbolah and Al Qaeda. I drew my last drawings from TV news -- the Twin Towers burning and falling. I was afraid then that the only thing worse than this attack would our response to it, and I certainly nailed that one. So the end of my book was also a terrible new beginning. Israel's reaction to an attempted assassination of an Israeli ambassador by Abu Nadal was to invade Lebanon which had nothing to do with it, just as our reaction to 911 was to attack Iraq which had nothing to do with it. Ironically, it was Sadam Hussein who had Abu Nadal killed in 2002. So it's a vicious cycle of misguided responses. So here it is. I've added a soundtrack from the music that inspired it, Mahler 5 and the Verdi Requiem. In his last Harvard lecture in 1973 Bernstein said the reason Mahler's music had been neglected for 50 years was that "It was simply too true … telling something too dreadful to hear." It was a premonition of death: Mahler's own death, the death of tonality and "the death of our society, of our Faustian culture." |

|||

|

3. Moments The evolution of a body of art work is like the evolution of a living body: natural selection from a series of random mutations. Theo Jansen is a Dutch sculptor who creates what he calls Strandbeests, or beach animals, out of pvc tubing. They walk along the beach, powered only by the wind. Watch this. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

Trailer for MOMENTS from Warren Criswell on Vimeo. |

|||

|

Yesterday I was looking through another old sketchbook of mine, The Green Notebook, and I found something amazingly relevant to this subject. I must have written it down after hearing an interview with Phillip Glass on the radio, back in June of 2001. It said that Phillip Glass finally understood Indian music after talking to Ravi Shankar. "Instead being divided into bars and measures as in Western music, it was made by adding the parts. In Western music there is an implied whole -- an empty but completed vessel -- which is divided up into its constituent parts, while in Indian music the whole emerges only as the sum of its parts. In our system there is an a priori essence which we divide into particulars; in the Indian system the 'essence' emerges as the sum of the particulars." And that's exactly what I've been talking

about. That's the way creativity works -- for me anyway. It's

a synergistic process, and it brings us back to Sartre's existentialism,

where existence precedes essence. So the body appears only after

its parts are assembled. Case solved!

|

|

All images and text on this Web site |