|

I read an article, a review, of a show of new

paintings at MOMA, in which the writer was lamenting that there

was nowhere new to go, aside from outlandish gimmicks, and therefore

painting was finished. It could bleed, he said, but not heal.

That was Peter Schjeldahl. But this is a misunderstanding of

creativity and not what Arthur Danto meant by "The End of

Art." It's true that this is the feeling that dominated

Modernism, whose main tendency was to eliminate everything considered

to be necessary to a work of art up until that moment - narrative,

verisimilitude, line, color, whatever - in search of the final

essence. It was a spiritual quest, really, in spite of some of

its phenomenological results, like action painting and minimalism.

But it was like the search for the Wizard of Oz, and it ended

- for me - in the '70s when Sol LeWitt eliminated the art object

itself. The final work was the concept, which in this case was

a list of instructions on how to make the painting or the "structure,"

as he called his sculptures. With the physical presence gone,

or unnecessary, there was nothing left to eliminate, no Wizard

behind the curtain. At least that's the way I saw it, and it

ended my futile pursuit of uniqueness. Or gave me an excuse to

end it.

Arthur Danto called it "The End of Art," and the three

of us are a good example. He meant the end of the linear history

of Western art theory: the progression from Romanticism to Realism

to Impressionism to Expressionism to Cubism to Abstraction to

Minimalism to Conceptualism. The end. After that there are no

more isms, no more manifestos, no more movements. We were

forced in upon ourselves, to find our own truths, our own personal

way to express them. It was only when I gave up my pursuit of

uniqueness and started trying to paint like the Old Masters that

people started saying my work was unique. Danto quotes Leonardo

da Vinci, ogni dipintore dipinge se ("every painter

paints himself").

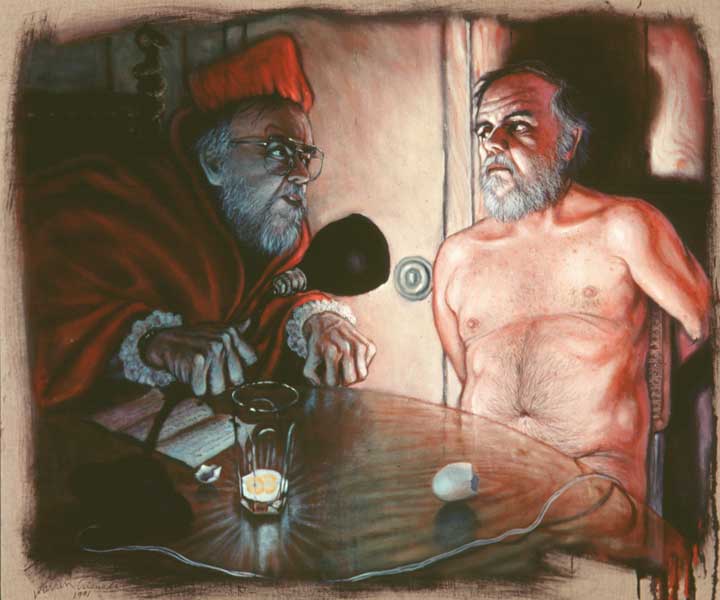

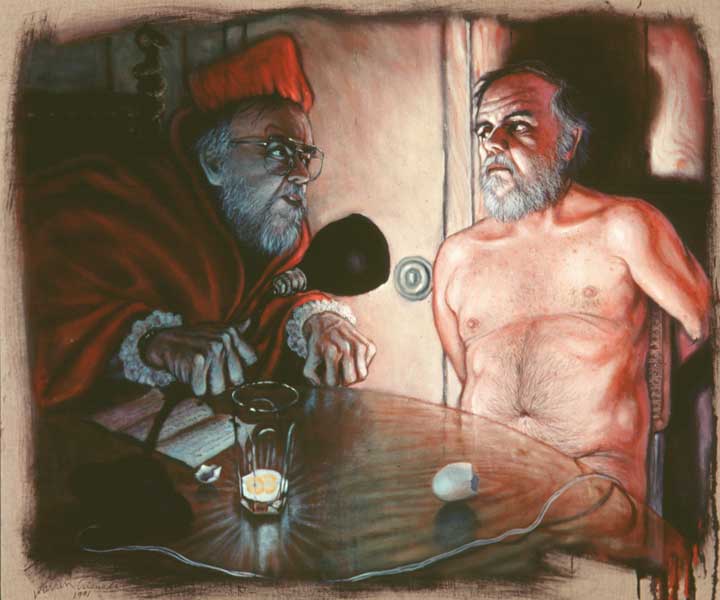

Warren Criswell, The Question, 1991, oil on linen, 36 x 43 inches (private collection) |

Sammy stayed with AbEx but let it evolve into

something difficult to categorize. Just as in a great symphony

you discover something new every time you hear it, every time

you look at a painting of Sammy's you see it differently.

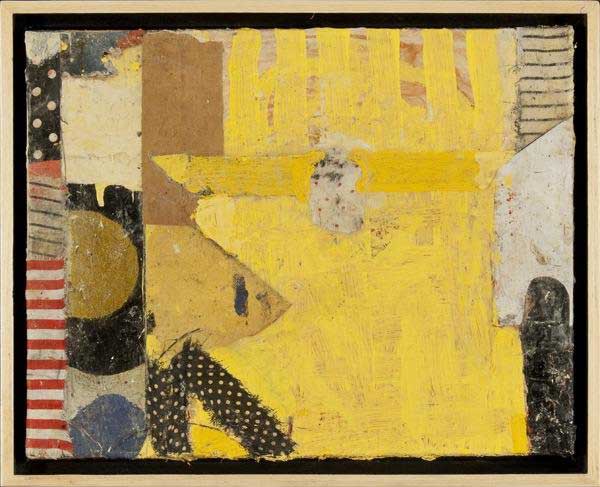

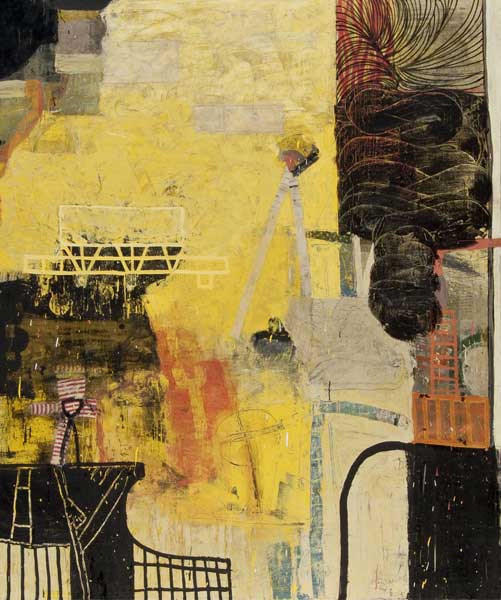

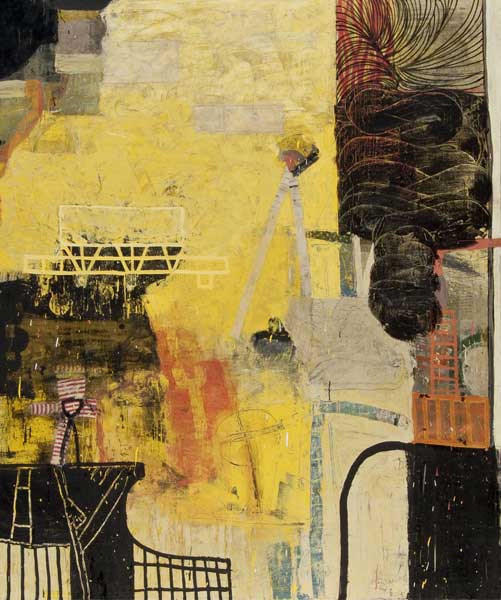

Sammy Peters, Impulse: significant; origin,

2015, mixed media on canvas, 52 x

68 inches (Remember that worm....) |

In the '80s, David, who had gone into theater

in response to the announced death of painting, now drifted back

into the graveyard of visual art, translating his scripts into

stark charcoal dramas on paper.

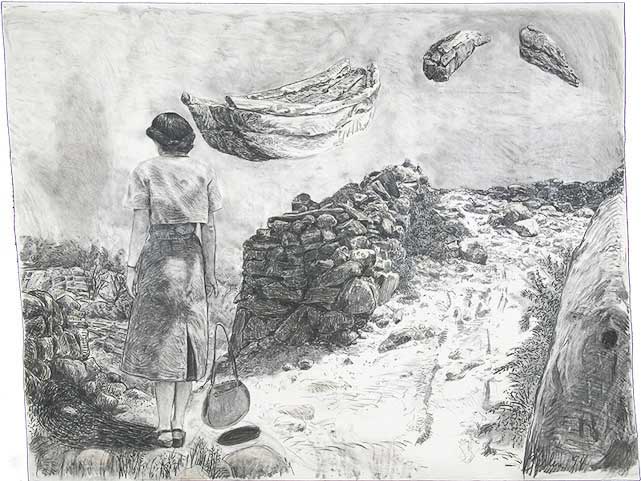

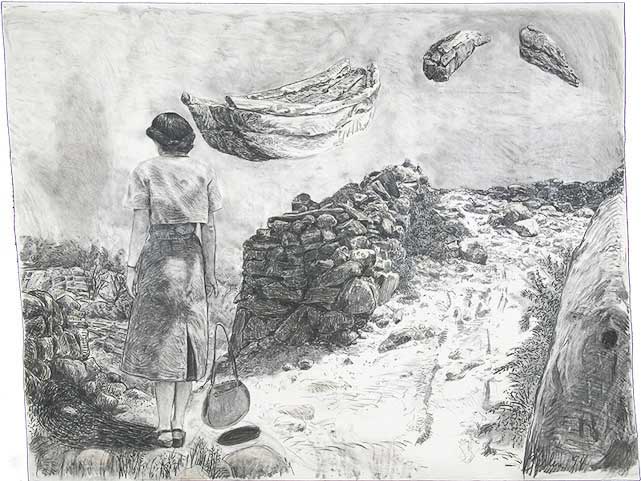

|

David Bailin, Salt (Lot's Wife), 1994, charcoal on paper, 96 x 144 inches

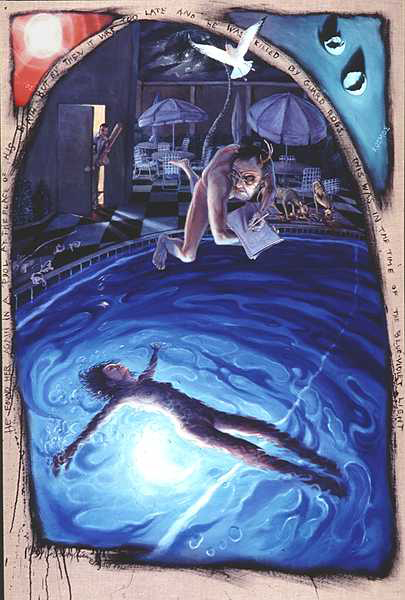

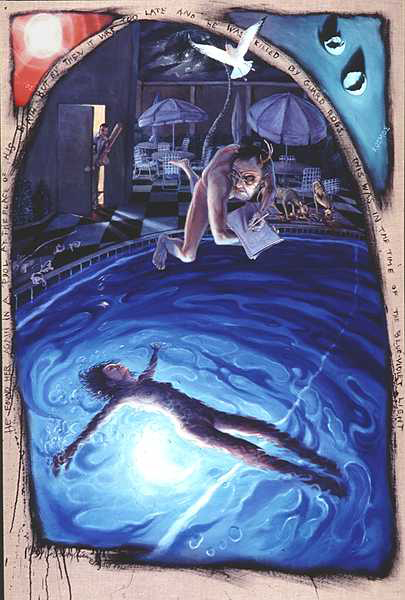

This reminds me of another similarity between

David and me in those days: we both looked back, like Lot's wife,

and we both defied gravity.

Criswell, The Pool, 1991,

oil on linen, 72 x 48 inches |

|

Because after Modernism there was no direction you had to follow.

It wasn't a dead end, it was a garden of forking paths, a liberation.

Artists were free to follow their own personal obsessions and

not be called reactionaries or dinosaurs.

Changes in styles and materials and media of course still happen

with social and cultural changes, but those are external. The

inner parts, the processes of creativity, don't change. They

are the same now as they were 35,000 years ago in Chauvet and

Altamira, and most of those parts are unconscious. Creativity

is mostly letting your unconscious override your conscious, rational

mind - the mind that tries desperately to become unique! - or

rather allowing it to give direction to your rational mind. But

creativity feeds on discovery, which means a change in perception.

So there's the problem: finding and executing changes in a changeless

process.

The true artist, the addict, like the three of us, can't keep

doing the same things over and over. We each took different paths

but we're alike in needing that fix, that hit, which is stumbling

across something new, a discovery, whether it's a sudden hypotenuse

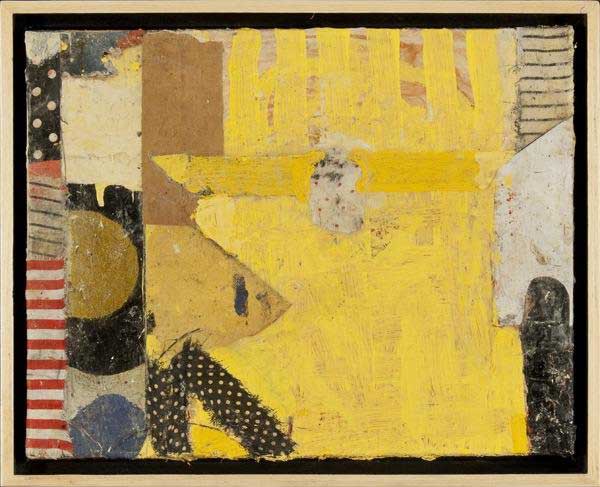

in a painting of rectangles ...

Sammy Peters, Transference: imagined; requirement,

2015, mixed media on canvas, 48 x

48 inches |

. . . or a concave curve in a model's thigh

. . .

Criswell, Psyche, 2012,

terracotta, 17 x 13 x 3 inches |

. . . or the way a stroke of paint looks over charcoal.

David Bailin, Raincoat, 2013,

charcoal,oil and coffee on prepared paper, 84 x 95 inches |

Yes, later we may find that we discovered that before, years

ago, but as long as we don't realize it at the time, we're good!

I remember David's despair when he thought he had exhausted Kafka

as a source . . .

David Bailin, Drip,

2013, charcoal on prepared paper, 52 x 54 inches (Now I'm seeing

cups full of blood: bleeding but not healing!) |

. . . the same way I felt when I had brought

my Grand Inquisitor series to an end.

Criswell, All the King's Horses, 1992, oil on linen, 48 x 36 inches |

And I know Sammy is as concerned about this as David and I, because

recently when I was cleaning out my bookshelves I came across

an interview in a magazine from 2003 (Pasatiempo, Sept.

12-18, "Pleasurable Tones" by Craig Smith, p.54), where

Sammy said, "When you look back at Pollock or de Kooning

or Rothko, it looks so serial." He said he knew there was

a progression in his own work too, but "the tone and mood

from one painting to the next can jump more dramatically"

than most of the guys he used to look at.

w.jpg)

Sammy Peters, Repose: significant; memory suite, No.10,

2015, mixed media on canvas, 11 x 14 inches |

|

Sammy Peters, Repose: significant; memory suite, No.16,

2015, mixed media on canvas, 12 x 16 inches

|

|

Sammy Peters, Repose: significant; memory suite, No. 9,

2015, mixed media on canvas, 11 x 14 inches

And those are all in the same suite!

|

So it's important for all of us to stay at

that edge - that doorway to the abyss that we haven't yet experienced

- or think we haven't. The trick is finding the door.

I read an article in the New Yorker about Yitang Zhang, the mathematician

who proved the "bounded gaps" problem, a 150-year-old

mystery of prime numbers, and he said exactly the same thing:

"Where is the door?" Like art, mathematics is a pursuit

of beauty, and you can't find it just because you want to or

have some formula to get there. Zhang said it was like "trying

to maneuver himself into a maze. When trying to prove a theorem,

you can almost be totally lost to knowing exactly where you want

to go." Finding your way, can happen in a moment, and "then

you live to do it again."

It's exactly the same with the artist. That's the addiction:

you live to do it again.

But that's not so easy. Art is artificial, but we want it to

be the truth. Our truth. An unsolvable conundrum. How to find

that door from artifice to truth? You can't find it because you

want to, it has to ambush you. This was Riggan's problem in the

movie Birdman, trying to get from comic book character

to serious stage artist, and he only found it by shooting himself

in the head. Benjamin Haydon and Mark Rothko found similar solutions.

Rothko didn't think people understood his work and were buying

it for the wrong reasons. (I'm not saying that's why he killed

himself, but it must have had something to do with it.) Haydon,

from Turner's time, had some success with the royalty at first

but was then ignored. Like Rodney Dangerfield, he didn't get

no respect. (Haydon shot himself but screwed that up too and

had to cut his throat.)

But those of us who are neither suicidal nor

able to cure our addiction have no choice but to keep hoping

to find those doors, going deeper into the maze. Or maybe trying

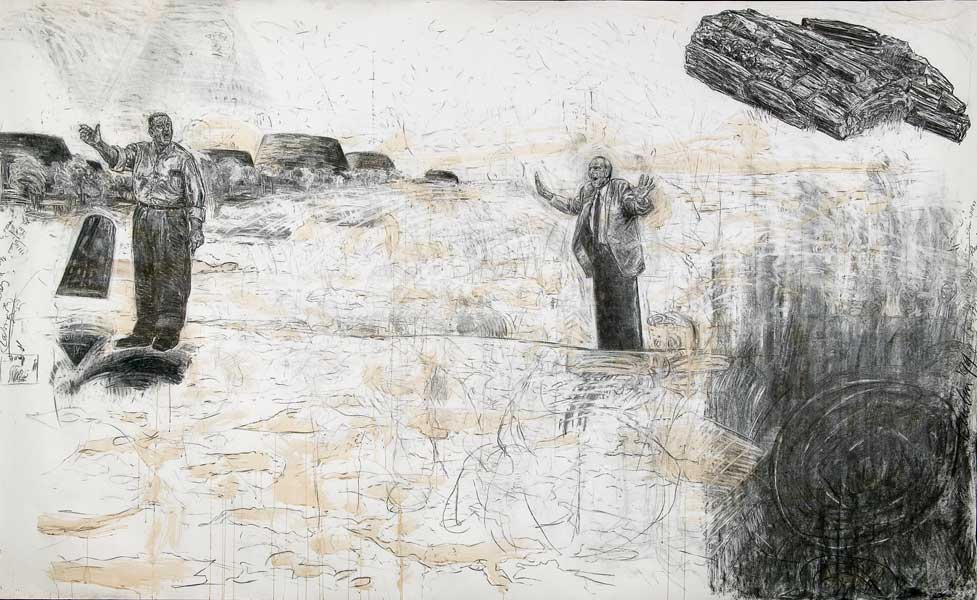

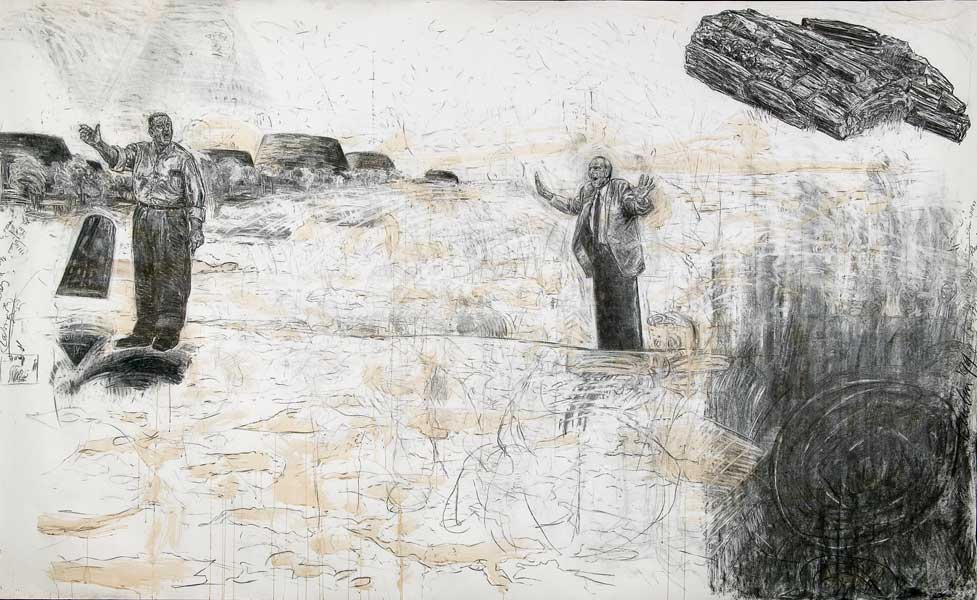

to get out. The maze, the labyrinth, keeps showing up in David's

drawings, from the early Midrash series to the recent

Dreams & Disasters.

PDavid

Bailin, Pryramid (Moses and Aaron), 1999, charcoal on paper, 96 x 157 inches (Here the

labyrinth is lurking darkly in the lower right.) PDavid

Bailin, Pryramid (Moses and Aaron), 1999, charcoal on paper, 96 x 157 inches (Here the

labyrinth is lurking darkly in the lower right.) |

|

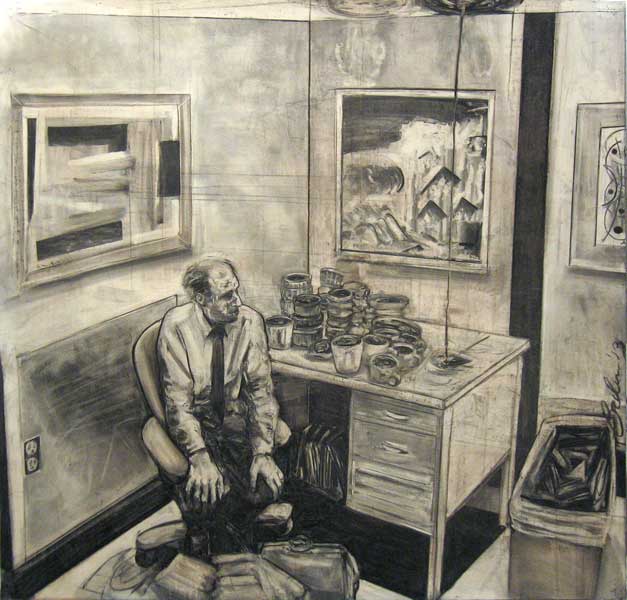

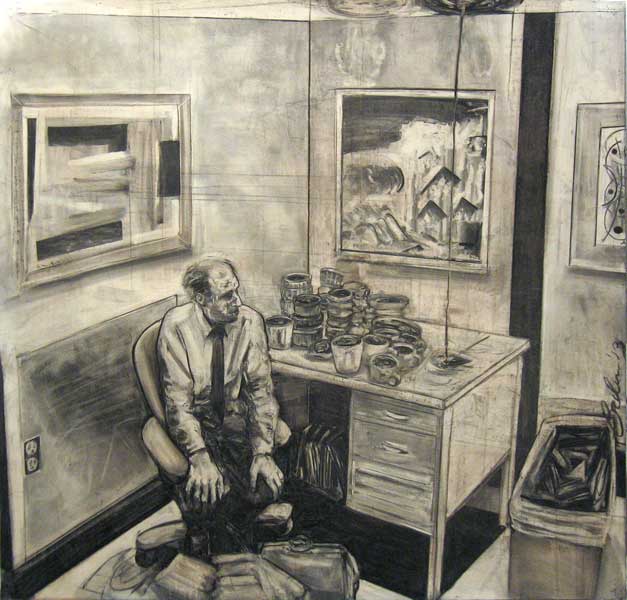

David Bailin, Papers,

2013, charcoal, pastel & coffee on prepared paper, 73 x 83

inches

(Here it whirls above the terrified bookkeeper, threatening to

swallow him up.)

|

Lately, I've been following the crumbs of my earlier work, back

out of the labyrinth, avoiding the Minotaur, making prints of

old images, hoping the Muse will take pity on me. But the Muse

has no pity. She will sing only when she's damn ready. All three

of us know the agony and terror of confronting a blank canvas

or paper, alone in our studios, and the joy when the lightning

strikes. And the fear when it doesn't.

Because the truth, the unknown entity lurking behind that door,

is not only an object of desire - it's also scary. We live our

normal lives on this side of the door, in a state of denial.

We have all the animal drives for pleasure and survival, but

we're the only animal that knows it was born and is going to

die. Art, religion and even science were born not only out of

our need to find order in chaos - to tell a story - but also

out of this terrible knowledge of our finiteness, our transience.

We ate that apple from the Tree of Knowledge and have been trying

to deal with the consequences ever since.

We hide our animal pleasures - which is why you didn't see my

videos in this

show (they were deemed a little too truthful for this

public venue) - and repress our human fears. This is necessary.

It's like when you're driving down the road, seeing only what's

necessary to get safely where you're going, editing out all the

rest. As Sherlock Holmes said, you're seeing, Watson, but not

observing. Observing can lead to dangerous things - like a wreck,

or a painting. To live our lives we have to steer a course down

the middle, avoiding the pleasures and the terrors, or else social

order would collapse. But the artist holed up in his or her studio,

in search of that monster Truth, doesn't have this luxury. We

have to try to find that door to what is either too much fun

or too scary - or, as in my case sometimes, both at once.

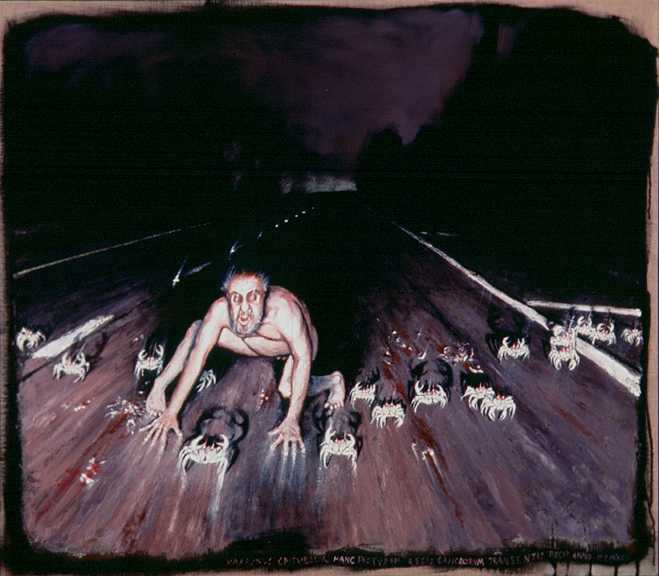

Criswell, Regis Cancorum Trahsentis (The Crab

King Crossing), 1991, oil on linen,

48 x 54 inches |

I see now that my Crab King Crossing expresses both desire

and dread! (The crabs are crossing A1A on the Florida east coast

to the beach for their annual spring orgy. A lot of them didn't

make it.) At the time I saw it as a confrontation with the Other,

and it is that too. But the Other only allows us to see ourselves

through his or her eyes. And the artist painting himself is his

own Other. Thinking also about my Dies Irae painting ...

Day of Wrath.

Criswell, Dies Irae,

1985, oil on canvas, 50 x 63 inches |

And I suddenly realized what the "worm" in some of

Sammy's paintings is! Many of his shapes and motifs, like David's,

have a way of reappearing and evolving in his paintings, and

one of them is this convoluted, twisted, tubular, organic looking

thing. Thinking about transference, as the psychologist call

it, is what led me to this interpretation.

Transference is kind of a tricky concept. According to Becker

and Jung, we transfer our fears and desires to an object - our

job, our family, whatever - thereby avoiding facing them directly.

But what if the object is one's art, which demands honestly confronting

both fear and desire? It looks like in that case transference

loops back on itself, feeding on itself like the Ouroboros, the

self-nourishing world snake. That's what Sammy's worm is! - to

me, that is, surely not to Sammy.

Here's one example - that black thing lurking on the right like

David's labyrinth, a python swallowing its tail.

Sammy Peters, Essence: inseparable; illusion, 2015, mixed media on canvas, 72 x 60 inches

(I know this isn't the way Sammy thinks

when he's titling his paintings, but this one could be read "Essence

is inseperable from illusion." That is pure phenomenology!)

|

Becker says, "The real world is simply too terrible to admit;

it tells man that he is a small, trembling animal who will decay

and die." But for the artist that too can be an inspiration!

For the artist the truth, no matter how terrible, can open the

door to his or her creativity, and as a creator, he once more

becomes a god who has conquered his mortality - even though he

has done it by confronting the very fact of his mortality! The

Ouroboros indeed. Art with a bite.

| Otto Rank

said that the artist must "step out of the frame" of

the ruling mindset, whether one's own or the culture's, and learn

how to unlearn. Creative solutions emerge from the fluctuating,

ever-expanding and ever-contracting, space between separation

and union. Art and the creative impulse, said Rank in Art and Artist, "originate solely in the constructive

harmonization of this fundamental dualism of all life" (Ernest

Becker, The Denial of Death) |

|

Another dualism of mine has been the

urge to push forward into the undiscovered and the equally strong

urge to look backwards, like Lot's wife, into the past. I love

the cave art of our early ancestors. Already they were pushing

into the unknown, creating images of animals - mammoths, aurochs,

woolly rhinos - which they subsequently hunted to extinction.

This duality is the terrible but unavoidable truth of being human.

Neanderthals, when they came to an ocean, stopped. Humans - differing

only in a few tiny genetic variations - built boats and kept

going. Neanderthals apparently had no interest in art or discovery.

They didn't look into the past or the future. If we hadn't come

out of Africa they would probably still be around, along with

the mammoths and aurochs, hunting with the same tools they had

used for a hundred thousand years. They didn't have the "creativity

gene," as some have called it. We might also call it the

"destructivity gene." Elizabeth Kolbert, in The

Sixth Extinction, put this way:

"With the capacity to represent the world in signs and symbols

comes the capacity to change it, which, as it happens, is also

the capacity to destroy it."

Which we are doing. Even as we create and discover new things,

we're sawing off the limb we're sitting on. This can be depressing,

but for an artist it can also be perversely inspiring, and it

has shown up in my art from time to time, as in Penthesilea

. . .

Cfriswell, Penthesilea (Love is a Dog Bite), 2011, 36 x 48 inches |

El Dorado . . .

1363w.jpg)

Criswell, Eldorado,

2013, oil on canvas, 30 x 40 inches |

. . . Two Men on Stilts, from back

in 1991, and many others.

Criswell, Two Men on Stilts, 1991, acrylic & oil on paper, 46 x 53 inches |

But now I realize that while this creative/destructive dichotomy

sometimes shows up in the subject matter of my work, it's actually

an integral part of David's and Sammy's process. David is working

on a series in which he rubs out everything he draws . . .

David Bailin, Red Tie,

2015, charcoal, oil, pastel & coffee on prepared paper, 72

x 84 inches |

And my favorite, a destroyed drawing from several years ago .

. .

w.jpg)

David Bailin, Destroyed drawing |

. . . in which only the ghosts are left. Even

the room is starting to fade.

And Sammy's paintings are also equal measures

of creation and destruction.

Sammy Peters, Momentary: accessible; appearance,

2015, mixed media on canvas, 72 x

60 inches |

If you look at them with an archeologist's

eye, you can imagine whole civilizations under the surface, created

and destroyed during the painting process, leaving only glimpses

of their past glory, like Ozymandias' trunkless stumps, eroding

in the desert. So in a way, their work is as scary as mine! If

I may translate another of Sammy's titles, "Appearance is

only momentarily accessible."

So even if the work we're producing in the

isolation of our studios is bleeding but not healing, as Schjeldahl

says, maybe that too can have the beauty of truth.

Warren Criswell

August 2015 |

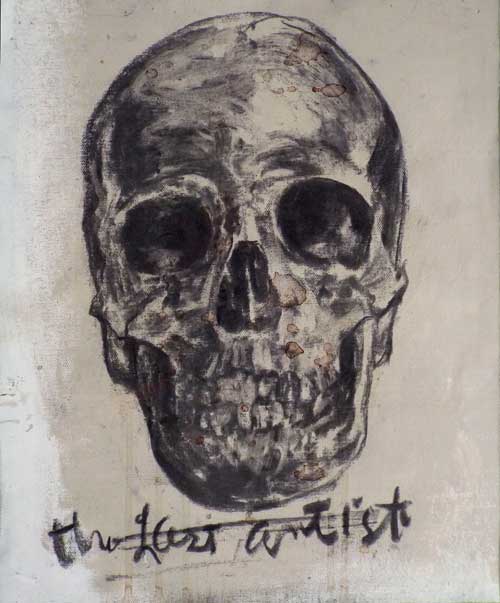

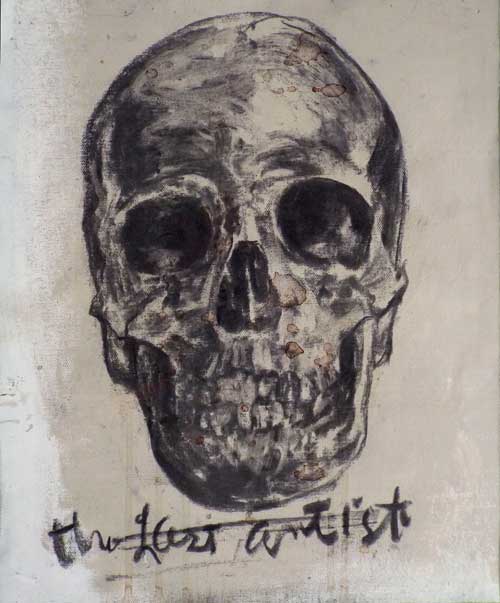

PS. At the risk of being morbid, I can't resist

giving David the last word:

David Bailin, The Last Artist, 2015, charcoal on gessoed

canvas, 11 x 14 inches |

|

w.jpg)

PDavid

Bailin, Pryramid (Moses and Aaron), 1999, charcoal on paper, 96 x 157 inches (Here the

labyrinth is lurking darkly in the lower right.)

PDavid

Bailin, Pryramid (Moses and Aaron), 1999, charcoal on paper, 96 x 157 inches (Here the

labyrinth is lurking darkly in the lower right.)

1363w.jpg)

w.jpg)